To celebrate the launch of our third collection with the Natural History Museum, we’re sitting down with some of the ‘unsung heroes’ of the NHM to learn more about their jobs and what they love most about working at the Museum!

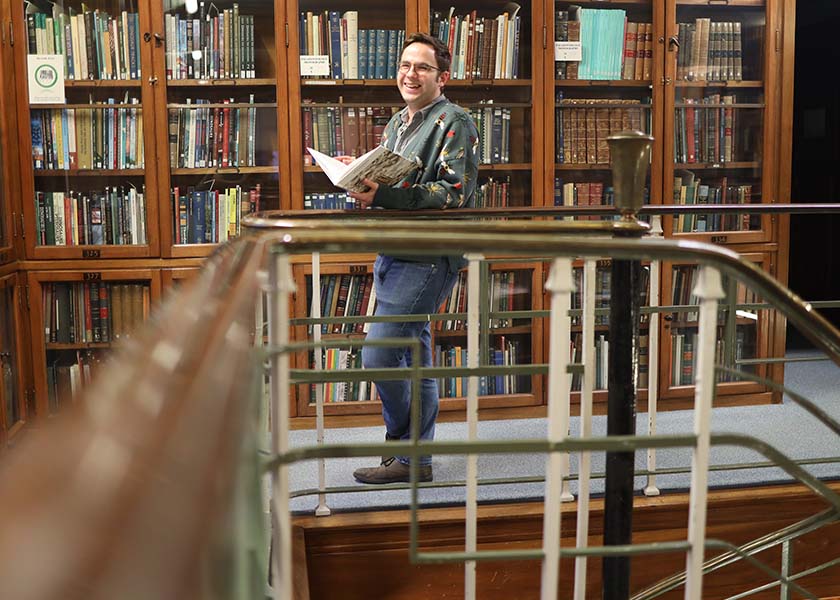

Meet Josh Davis, Digital News Editor

Hi Josh! Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and your career so far?

I am the Digital News Editor for the Natural History Museum. This basically means I spend my days reading, writing and editing about all the amazing science that is being done at the Museum.

While most people might think that the Museum is simply a dusty collection of old bones, there is actually a huge, vibrant team of scientists working behind the scenes. Not only are they caring for the collections, which are continually being added to and in need to curation, but they are also doing active research on everything from how whales evolved to look how they do to the very origins of planet Earth itself.

My job is to find out what these people are working on, talk to them, and then write about their research in a way that is engaging, exciting and accessible. The more people who know about the incredible work our scientists are doing to better understand the planet, the threats it is facing, and - most importantly - how we can solve them, then the better.

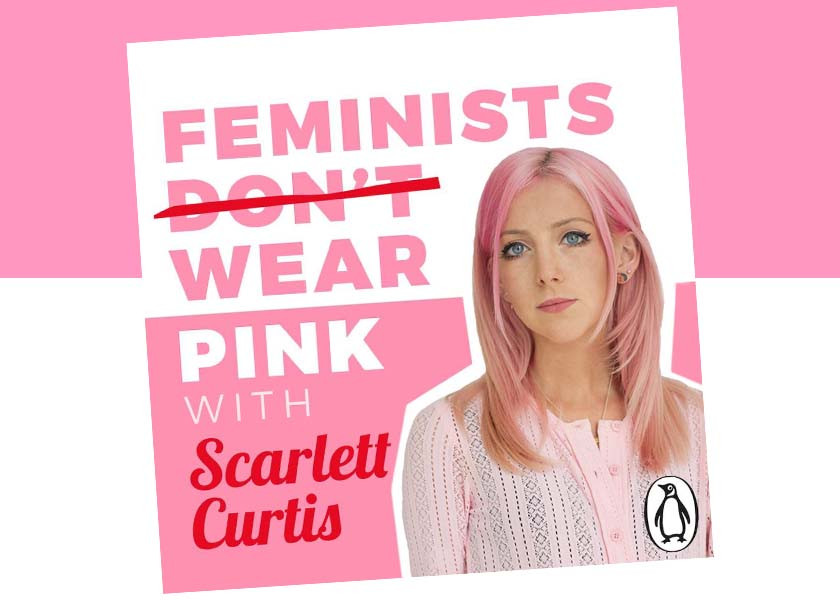

I have also recently written a book for the Museum! I have a keen interest in queer history, having co-produced, written and delivered the Museum’s first ever LGBTQ+ Natural History Tour, which I’ve spent the last year writing up into a book.

Currently titled A Little Gay Natural History, it covers a whole range of non-heteronormative behaviours in the natural world, from butterflies that embody male and female biological tissue in the same body, how temperatures of turtle eggs determine their hatchlings’ sex, to a tomato that can reproduce three different ways at the same time. It will be published in the second half of 2023, so what this space!

What made you want to work at the Natural History Museum?

As is the case with a lot of us who work here, I have been coming to the Natural History Museum since I was a child. This almost certainly played a part in influencing me to go on to study zoology at university and eventually work my way into science writing.

I also genuinely love talking and writing about nature and love telling people all the weird and wonderful facts I come across. For example, did you know that sharks are older than trees? Or that all the spiders in the world eat more prey per year than all the whales in the world?

So, working at the Museum is really a natural history nerd’s dream come true.

What’s the most exciting thing about your job?

Easily the fact that I get to talk to so many amazing people and see so many incredible specimens from the collections.

My job means that I work with scientists from right across the Museum, from people studying the pieces of asteroid to those describing new species from the bottom of the deepest oceans. This means that I’m lucky enough to see a huge range of the collections. I’ve stood next to the skull of a blue whale, held a piece of rock that is as old as the solar system itself and stroked the fur of the now extinct thylacine. You’d probably be hard pressed to find someone who has seen a wider breadth of the Natural History Museum’s extraordinary collections than I have.

In addition to that, writing about the work that our scientists do means that I have also been fortunate to join them on a few of their field trips. Out of these, going on a dinosaur dig to South Africa probably has to be top of the list. This involved spending almost two weeks living in a remote village in the highlands, uncovering fossils of dinosaurs and reptiles dating to the Late Triassic, so roughly 200 million years ago. Not much prepares you for being the first person to ever set eyes on a fossil that old!

What’s your favourite thing in the Natural History Museum’s collections and archives and why?

This might be a bit of a cheat, but all of the moa specimens in the collections.

The moa were huge, ostrich-like birds that lived in New Zealand up until around 500 years ago. There were a few different species, with some smaller ones acting like grazing sheep while the truly massive ones were browsing on leaves and branches a bit like moose. Unfortunately, following the arrival of humans to New Zealand, they were all hunted to extinction by 1445.

What is amazing is that not only does the Natural History Museum have a whole bunch of moa bones, but also an extraordinarily rare moa egg, moa footprints, moa poop and - wildest of all - an actual mummified moa head and foot. The only known mummified moa head in existence, you can literally stare into the face of an animal that went extinct when Henry VI was on the throne. That blows my mind.

What advice would you give to someone looking to follow in your footsteps or to somebody who aspires to work at the NHM?

Write! It doesn’t matter who you’re writing for or what you’re writing - the only way for you to learn and grow is to start putting some words down on that page. If you’re struggling, then start a blog and write about something you love - it could be a hobby or interest, it doesn’t really matter.

It might sound a little trite, but if you don’t know how to begin, I genuinely find the best way to get going is just to start writing something you know you want to include and then build everything else around that. It doesn’t matter if it is the start, middle or end. In fact, I often start writing the middle of a piece first, and write the beginning last.

Once you’ve got a little back catalogue with something to show, then it becomes much easier to start pitching to editors as they can see your style and interests. Before pitching, always check that what you’re proposing is a fit for the publication you’re aiming for. Have a look at what they’ve done in the past and if you’re happy with their style and approach.

The second piece of advice is, when pitching, to not be afraid to follow up. Editors are busy! They get a lot of emails in any one day, and so it is easy to lose sight of pitches. A polite prod a week or so later is not to be unexpected.

Writing for a living is a tough career, and that is not to be over simplified, but once you get your foot in the door, then be sure to keep it there and carve out your own little niche so that, eventually, people come to you.